C. diff, or Clostridioides difficile, is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped, anaerobic, endosporic, toxigenic, opportunistic, bacillus. Its scientific description makes it sound like a pretty standard bacteria. But this bacteria "causes almost half a million infections in the United States each year" according to the CDC. November is C. diff Awareness Month so stick with us all month to learn more about this microorganism and the unique attributes that make it so lethal. Today’s post will explore the basic definition of Clostridioides difficile. First, let’s unpack that long list of terms mentioned above.

Clostridioides difficile:

Clostridioides, from the Latin for “spindle,” (for its rod shape) is a genus of bacteria that can claim membership of not only C. diff, but also the pathogens that cause botulism, food poisoning, cellulitis, and tetanus. (What a family!) This particular member was named “difficile,” for “difficult” or “obstinate,” a perfect name for a pathogen that resists medical treatments as well as cleaning regimens.

Gram-positive:

As a Gram-positive bacteria, C. diff has a thick protective layer over its cell membrane. In most cases, gram-positive bacteria are more vulnerable to antibiotics. If they do develop resistance, it is due to special resistance genes that happen to be located on parts of the DNA that can split off and move, making more copies of themselves and sharing their code with other neighboring cells. Unfortunately, C.diff has a lot of these mobile resistance DNA segments. As a result, C. diff is highly resistant to antibiotics.

Anaerobic:

Obligate anaerobes like C. diff cannot survive in an oxygen atmosphere; oxygen is not required for growth or energy, and is in fact toxic. An evolutionary adaptation has allowed C. diff to persist in an oxygen atmosphere, however: spores.

Endosporic:

Endosporic:

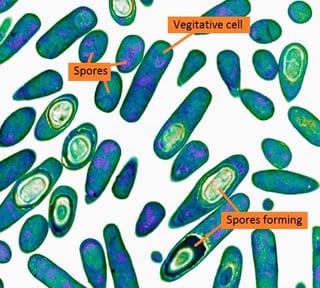

C. diff’s greatest defense against natural and human attacks is its ability to create spores. These drumstick-shaped armored tanks are created when a regular (vegetative) cell sends most of its DNA into a little packet inside itself, wraps that packet up in layers and layers of hard membranes, and then ruptures to let the spore escape. This armored DNA packet can survive intense heat, alcohol-based cleaners, and stomach acid. This means that when it is present on a surface, it can survive there for years, without nutrients, where it can be picked up by a hand, transferred to a mouth, and is ingested. Unlike other bacteria, C. diff spores are not destroyed by stomach acid, so they proceed to the digestive system, adhering to the lining of the small intestine, and germinating into regular cells again. And the cycle repeats over and over again.

Toxigenic:

Once the spore germinates and produces regular, vegetative cells, the metabolic processes of the pathogen begin to poison the host. Each cell releases two types of toxins into the body, proteins that damage the epithelial tissue lining the intestine causing inflammation, severe diarrhea, and even death. In some cases, such as when the host has a healthy immune system, the infection is contained and can be treated. In fact, some individuals are colonized with C. diff but never develop symptoms. They can still spread the disease, however, as they shed spores just as often as those showing symptoms. Once released into the environment, the spores are ready for their chance to germinate and reproduce to keep the cycle going.

Opportunistic:

And C. diff gets its chance, especially in hospitals, long-term healthcare facilities, and nursing homes. In these locations, many patients are undergoing treatments requiring antibiotics. Antibiotics destroy pathogenic bacteria in these patients – along with commensal (helpful) bacteria in the patient’s gut. With the patient’s microbiota so severely reduced, any ingestion of C. diff provides the pathogen with a threat-free landscape to take over with impunity. With very few other bacteria to compete with for nutrients and space, C. diff, an opportunistic pathogen, quickly takes over. Studies show that patients taking antibiotics have a 7-fold increase in their chances of getting a C. diff infection, and C. diff is responsible for 15-25% of all antibiotic-related cases of diarrhea.

Now that we have a better idea of this pathogen, we are ready to delve into the disease. What are the risk factors? Who is the most vulnerable? What are the stages of the disease? What are the available treatments? We'll cover this in next week's post!

Editor's Note: This post was originally published in April 2016 and has been updated for freshness, accuracy and comprehensiveness.

![EOScu Logo - Dark - Outlined [07182023]-01](https://blog.eoscu.com/hubfs/Eoscu_June2024/Images/EOScu%20Logo%20-%20Dark%20-%20Outlined%20%5B07182023%5D-01.svg)

![[infographic] Stopping the C. diff Cycle Download and share!](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/216314/interactive-178280319550.png)