What are QALYs and DALYs?

How do you put an economic value on a human life? Why would you ever want to? As difficult as this quantification may be, it is a necessary practice in healthcare when evaluating the efficacy of an intervention, the appropriation of resources, as well as the framing of options for both the individual and a population. Two measures attempt to accomplish this valuation: Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). In the next series of posts, we will explore both these measures, and ultimately discuss how they are used in the field of infection control and prevention.

How do you put an economic value on a human life? Why would you ever want to? As difficult as this quantification may be, it is a necessary practice in healthcare when evaluating the efficacy of an intervention, the appropriation of resources, as well as the framing of options for both the individual and a population. Two measures attempt to accomplish this valuation: Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). In the next series of posts, we will explore both these measures, and ultimately discuss how they are used in the field of infection control and prevention.

Put simply, "QALYs are years of healthy life lived, DALYs are years of healthy life lost." Both measures consider years lived and quality of life, but while QALYs use "utility weights," that is, what the patient can do despite the medical condition, DALYs use "disability weights," that is, the burden of the medical condition on the patient. QALYs measure quality of life gained while DALYs measure years lost to disability and/or premature death. So how are these measures determined?

QALYs | Years of healthy life gained | Scored by individuals

Would you rather live 10 years with a disease or 7 years in perfect health? How about 5 years of perfect health? Would you take the risk of a healthcare intervention to cure that disease if there was an 80% chance of cure but a 20% chance of death? How about a 10% chance of death? These are the questions used to determine an otherwise hard-to-measure concept: quality of life. Using lessons from game theory, which attempts to pick out the complex choices used in decision-making, researchers came up with two ways to put numbers to quality of life. ![]()

NOTE: The following two methods are used with test subjects who are not considering health treatments. These methods are not used when actually helping a patient make decisions, only to help inform the patient and researchers about how large groups of people feel about similar questions.

The first is called the "Time Trade-Off," and asks those participating in the survey to choose between x number of years with a condition vs. y number of years in perfect health, varying x and y until the individual is no longer willing to "trade off " years lived in exchange for health. For example, someone is asked whether they would be willing to live 10 years with their current health state of, say, diabetes, or 7 years of perfect health. In response to this completely hypothetical scenario, they choose 10 years with diabetes as preferential to 7 years of perfect health. The iterative questions continue, with the option of 10 years with diabetes or 8 years of perfect health. The questions continue until the individual is indifferent about the choices; they feel both are equal. If the final numbers are 10 years with the condition and 8.5 years of perfect health, the "value of health" reduction of the condition would be 15%. For this condition, the average score reveals that living with the condition reduces quality of life by 15%.

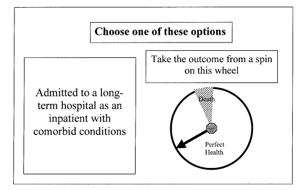

In addition to the Time Trade-Off, another set of iterative questions is used called "The Standard Gamble". In this method, test-takers are asked about their willingness to risk a medical intervention where there is an x% chance of immediate death and a y% chance of restored full health. (In both cases, the individual would live the same number of years.) Here is an example from a standard gamble survey:

From "Health Utility Measures and the Standard Gamble," Garza and Wyrwich, 2003.

Both of these measures results in a "health utility" value, which researchers can use in their formulas to calculate QALY: The change in health utility value multiplied by the duration of the effect of the intervention = the number of QALYs gained. The QALY is expressed as a number from 0 to 1, with 0 being no quality of life (death) and 1 being full quality of life at perfect health. The goal of interventions under this model is not necessarily to reach 1, but rather, to demonstrate gains from, say, a .4 to a .6, which would be expressed as "a gain of .2 QALY." Of course, one person's ".6" may not be another person's ".6," but a gain of .2 has been demonstrated to be consistent enough to make medical decisions.

![]() QALYs are often used to measure cost-effectiveness of an intervention, especially in countries where mortality is already reduced (allowing quality of life to be given greater priority, most often, high-income countries). QALYs can be helpful in choosing between two health interventions, especially when one is riskier than the other, as it informs the patient about what they can expect to see in improvements and allows the patient to consider choices alongside risks.

QALYs are often used to measure cost-effectiveness of an intervention, especially in countries where mortality is already reduced (allowing quality of life to be given greater priority, most often, high-income countries). QALYs can be helpful in choosing between two health interventions, especially when one is riskier than the other, as it informs the patient about what they can expect to see in improvements and allows the patient to consider choices alongside risks.

While QALYs measure how many years are lived in good health, DALYs measure how many healthy years of life are lost to disease. For that analysis, tune in next week for our in-depth look at DALYs!

![EOScu Logo - Dark - Outlined [07182023]-01](https://blog.eoscu.com/hubfs/Eoscu_June2024/Images/EOScu%20Logo%20-%20Dark%20-%20Outlined%20%5B07182023%5D-01.svg)