What is the Microbiome?

One of the fastest-growing research sectors is the investigation of the human microbiome. We read articles about using the microbiome to keep us healthy and even to cure us from disease. What is the microbiome? In today’s post, we’ll explore this invisible but essential part of our existence.

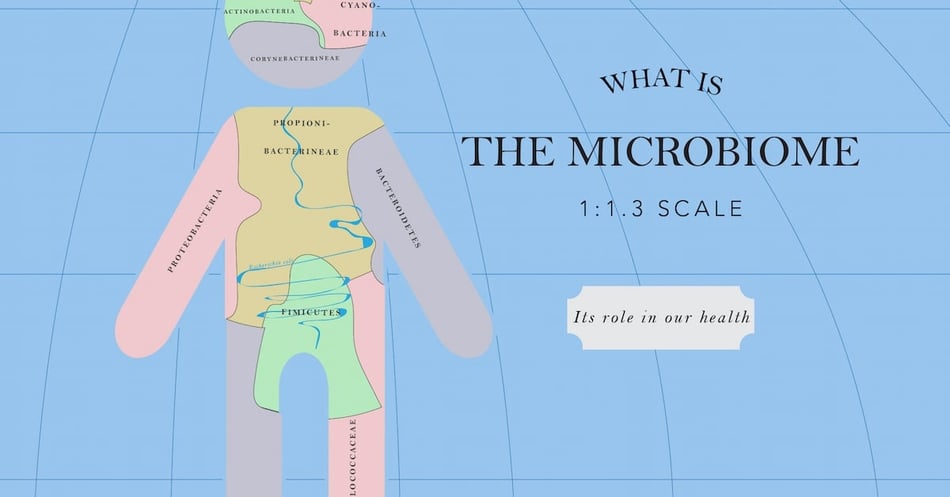

A biome is a naturally-occurring community of lifeforms living in one type of habitat. A biome could be a tundra, a coral reef, or a desert oasis, and is populated by animals and plants that live together in a complex web of relationships. By adding the prefix micro, we get a microbiome, populated microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses. And the habitat? Our bodies.

There is tremendous research into this area, but the largest is NIH's Human Microbiome Project, whose task is to fully explore the microorganisms that live in and on our bodies and how they contribute to human health and disease. Where the Human Genome Project sought to sequence human DNA, the Human Microbiome Project seeks to identify and sequence the many microorganisms that call our bodies home.

We spend our first months of life in a sterile womb, too fragile to handle a microbiome of our own. But our mothers’ microbiome changes during pregnancy, reaching a good mix of bacteria to pass over during childbirth. During our first three years, we collect and adjust our own microbiome, picking up necessary bacteria from breast milk, food, the environment, and other sources. As we grow up, our microbiome is affected by where we live, what we eat, any drugs we take, and other factors. But what remains the same is that we go through life with a microbiome of a vast array of bacteria who outnumber our own human body cells by just about 1.3:1.

Just like human DNA, our microbiome differs from person to person while retaining an overall pattern. There are microorganisms that populate specific body parts, everything from our GI tract, our respiratory system, our skin and our mucous membranes. Without these microorganisms, our health would suffer: We would be more vulnerable to infection, we would suffer from poor digestion leading to nutrient deficiencies, and many more ailments. We evolved to depend on our bacterial passengers.

Studies have revealed even more subtlety in the interplay between our microbiome and our body. Some studies seem to demonstrate that our gut bacteria has a direct impact on our weight, with some bacterial communities closely associated with obesity, depression, and possibly even autism and diabetes. Other research shows that certain microbiomes can make chemotherapy and other drug therapies more effective. While further research is needed, it seems as if we are more affected by our microbiome than we ever thought possible.

The ability of our microbiome to affect our health means that medical interventions could be developed that use microorganisms that might even cure us of certain diseases. One such intervention has already proved successful: Patients with C. difficile infections often respond very well to having their gut bacteria replaced with that of a healthy person. Future therapies might involve using microbiome adjustments to help with mental health, weight control, diabetes, and other chronic conditions. We may even get to a point where we can adjust the genome of specific bacteria in order to target specific diseases.

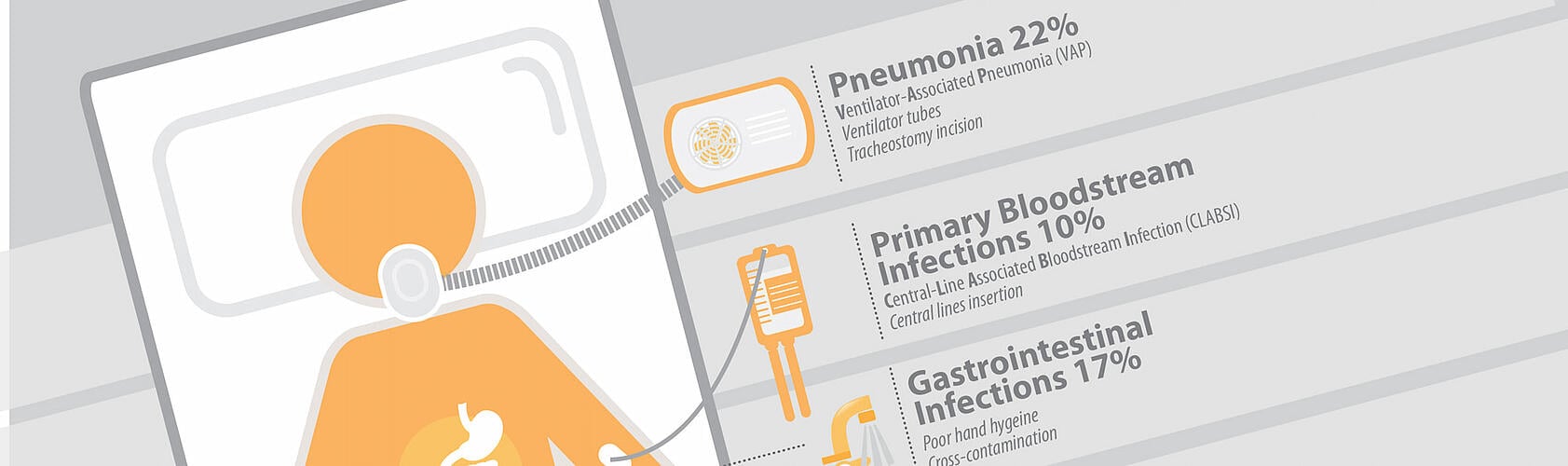

Infection control and prevention specialists spend their whole professional lives waging war with the microbiome. Washing hands, giving chlorhexidine baths, dressing surgical sites, removing indwelling devices - all these activities serve not only to avoid exogenous infections, but to also protect patients from their own endogenous microbiome. As all infection preventionists know, any unbalance in the microbiome can make a patient more vulnerable to an opportunistic infection, one that takes advantage of a weakness in a person's microbiome to colonize and infect. It will take several more years of research, but maybe one day these healthcare workers will have tools that allow them to enlist a patient's own microbiome in the fight against hospital-acquired infections!

Editor's Note: This post was originally published in April 2019 and has been updated for freshness, accuracy and comprehensiveness.

![EOScu Logo - Dark - Outlined [07182023]-01](https://blog.eoscu.com/hubfs/Eoscu_June2024/Images/EOScu%20Logo%20-%20Dark%20-%20Outlined%20%5B07182023%5D-01.svg)

![[infographic] 3 Reasons Patients are Vulnerable to HAIs Download and share!](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/216314/interactive-178382222189.png)