Emerging Viral Pathogen Claims: How Products Make Claims About New Pathogens

As soon as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) identify an emerging pathogenic virus that is either completely new or starting to spread into new geographic areas, they trigger a process that leads to us, the consumers. When a new pathogen starts to spread and cause disease, and if the CDC recommends that environmental surfaces be disinfected to help slow the spread, then the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) must provide guidance on which products can make the claims that they kill the emerging pathogen. In today's post, we'll look at the series of events, and what steps products must follow to achieve this public health claim.

As soon as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) identify an emerging pathogenic virus that is either completely new or starting to spread into new geographic areas, they trigger a process that leads to us, the consumers. When a new pathogen starts to spread and cause disease, and if the CDC recommends that environmental surfaces be disinfected to help slow the spread, then the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) must provide guidance on which products can make the claims that they kill the emerging pathogen. In today's post, we'll look at the series of events, and what steps products must follow to achieve this public health claim.

As we've covered before in this blog, the EPA is responsible for ensuring that products that make claims that affect public health are being truthful and are backed up by evidence. To that end, products making public health claims about being able to kill pathogens that cause illness must go through a rigorous process to be registered with the EPA, and then follow their approved labelling language precisely for total transparency with the customer and user. For example, EOSCU is registered for public health claims that are precisely defined by what it kills (Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria), how long it takes to kill it (under 2 hours), and to what extent (3 log reduction, or 99.9%).

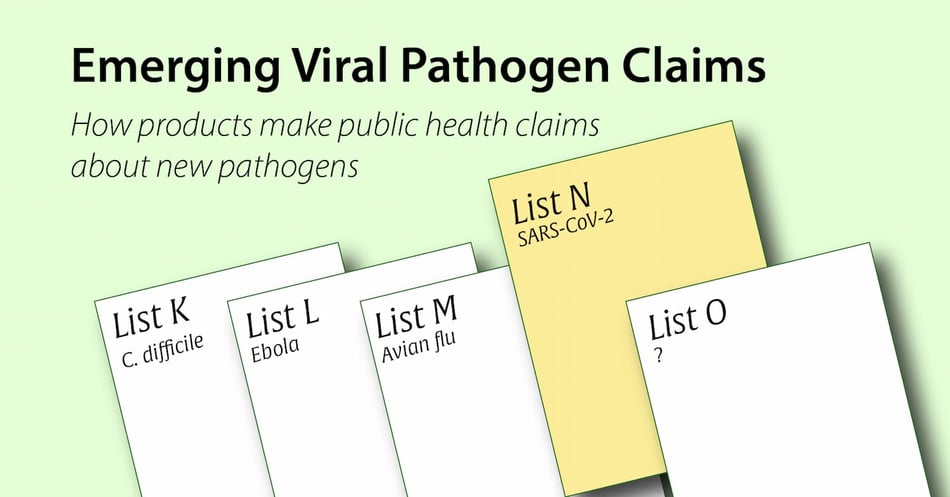

But what about when a new pathogen emerges? In order to get helpful products into the hands of healthcare facilities and people at home, the EPA needs to have a way to approve public health claims quickly. As a result, in 2016, the EPA created the emerging viral pathogen claim process, which allows products to demonstrate efficacy against harder-to-kill pathogens or a pathogen surrogate in order to make public health claims against a brand-new pathogen. Products that meet the criteria must have their label language approved by the EPA, which they can then use in marketing materials, presentations, and social media.

All the products that go through this process are then put together on a special list published by the EPA. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, this list was called "List N." Other lists have come and gone with previous outbreaks: List M is for avian flu, while List L is for Ebola. The list is made up of products that the EPA expects will kill the emerging virus.

So how does a product go about getting on this list? One way is to demonstrate efficacy in a third-party laboratory against a surrogate pathogen. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, a surrogate human coronavirus was accepted. A more proactive way to get onto current and future lists is to demonstrate efficacy in a third-party laboratory against a harder-to-kill pathogen. For example, feline calicivirus (FCV) is considered the hardest to kill virus. Any product that demonstrates efficacy against FCV would be considered for inclusion on a future list of products. In both cases, products must submit an official request for inclusion along with testing documentation.

The EPA ensures transparency with the general public about what products can and can't do when it comes to public health. When customers know the exact parameters of a product, they are better able to choose what works best for their needs. In the case of an unexpected, unpredictable pathogen, the emerging viral pathogen claim process balances the need for a rapid response with the need for an informed, trusted response.

![EOScu Logo - Dark - Outlined [07182023]-01](https://blog.eoscu.com/hubfs/Eoscu_June2024/Images/EOScu%20Logo%20-%20Dark%20-%20Outlined%20%5B07182023%5D-01.svg)