The Most Common Sites and Types of Hospital Acquired Infections

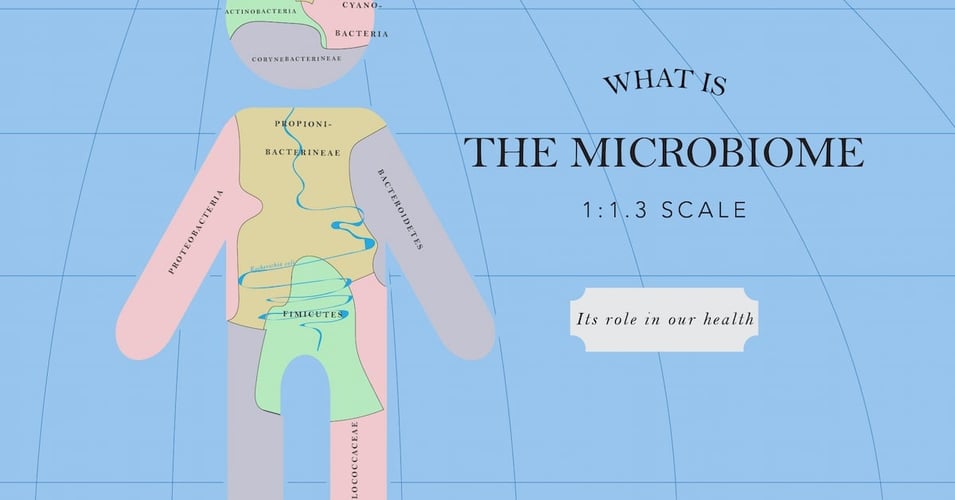

We are all covered in bacteria. (You could even say we are all contaminated.) Bacteria and other microorganisms live in our gut, in our mucous membranes such as our nostrils, on our eyelashes, and in our bellybuttons. We do not consider ourselves infected, however, because these organisms have not crossed the barrier of our skin to enter our tissues, muscles, bones, and body cavities. These deep parts of our bodies are basically sterile - no microorganisms live there at all. As long as our protective barriers are not breached, we remain healthy. The "contamination" is just part of our microbiome, our own personal little collection of life that we carry around with us all the time. This microbiome is made up of colonies of bacteria, groups of same-species bacteria that live and die without our even being aware of them.

That is, until our skin is breached. Of course, we sustain minor cuts in our lifetime. Those cuts allow the germs that live with and on us every day to enter our bodies and reproduce - creating an infection. As healthy individuals, we clean our cut with an antibiotic, keep it clean, and meanwhile, our immune systems kick in, and soon enough we don't even remember we had a cut. We have a general resistance to infection. In this case, resistance means we can fight it off without outside assistance.

However, some of us are more vulnerable and less resistant to infection. These individuals include newborn babies, whose immune system is not as well developed, the elderly, whose immune system response has slowed, and those with an underlying illness or severe injury, whose immune system has been compromised. Let's look more closely at those individuals who are patients in an acute health care setting like a hospital.

Individuals who are receiving life-sustaining care in a hospital are not only vulnerable to infection due to their compromised immune system, they may also be dependent on a medical device that, in order to do its job, breaches the barrier of the skin. Through contact with a contaminated surface, this device can become contaminated, and as a result, the patient is infected.

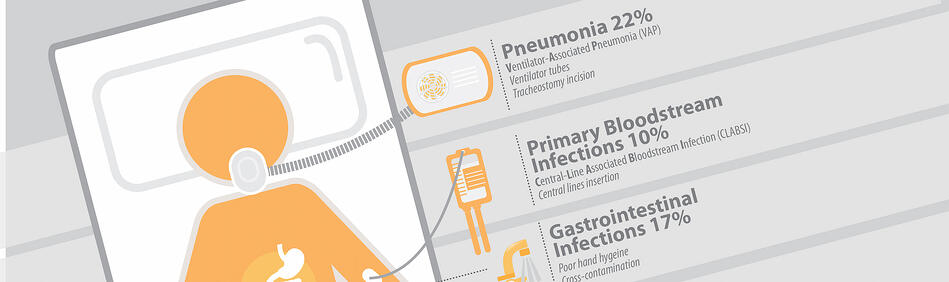

Just over a quarter (26%) of hospital-acquired infections are associated with medical devices that pierce the skin or enter the body. These include central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). There are other sources of infection, as described below.

What are the most common hospital acquired infections?

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

Pneumonia and other respiratory or lung infections are often associated with the use of a ventilator and account for 22% of all HAIs. A ventilator assists the patient with breathing with tubes which enter the body via the mouth, nose, or incision in the throat. Germs can enter the ventilator and therefore be transported to the lungs.

Gastrointestinal infections

The gastrointestinal tract is an organ system made up of all the organs responsible for digesting food and excreting waste. These organs are home to billions of naturally-occurring bacteria, including e. coli. When the healthy balance of these bacteria is upset (for example, by the use of antibiotics), or a foreign bacteria is introduced, infection can set in. GI infections lead to contaminated waste as the body tries to remove the infection in the form of vomit and diarrhea. This waste can lead to further contamination, especially if cleaning is not thorough and frequent.

Urinary tract infections (CAUTIs)

When germs enter the urinary system, often via a catheter, infection can affect the bladder and even the kidneys. 14% of all HAIs are UTIs, and like other device-associated infections, are usually caused by contact with a contaminated surface or through the air.

Primary bloodstream infections (Central line-associated bloodstream infections, or CLABSI)

Sometimes infections are present in the bloodstream. This means that the germs are present in the bloodstream itself. These infections are categorized as "primary," which means the bloodstream was the first area infected, or "secondary," which means that the bloodstream became infected as a result of another infection elsewhere in the body. Primary bloodstream infections, which account for 11% of all HAIs, are overwhelmingly (84%) associated with the use of a central line. A central line is a tube which enters the body through a large vein and provides the patient with fluids, blood, or medications.

Surgical site/wound infections

In addition to the device-associated infections, wounds and surgery sites are also locations of HAIs. In fact, 22% of hospital-acquired infections effect surgical incision sites and may include the skin or deeper tissue and/or organs. Infections may also involve an implanted device or material. These infections can occur days or even months after surgery as the incision heals.

Once the protective barrier of our skin is crossed, our bodies do have ways to fight off infection. Our immune system can send in antibodies, raise our temperature, increase blood flow, basically waging war with harmful pathogens. However, individuals with compromised immune systems, like those who are already sick or injured, are much more vulnerable to hospital-acquired infections. We'll look at these individuals next week.

Editor's Note: This post was originally published in November 2014 and has been updated for freshness, accuracy and comprehensiveness.

![EOScu Logo - Dark - Outlined [07182023]-01](https://blog.eoscu.com/hubfs/Eoscu_June2024/Images/EOScu%20Logo%20-%20Dark%20-%20Outlined%20%5B07182023%5D-01.svg)

![[infographic] Sites & Types of HAIs Download and share!](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/216314/interactive-178207379828.png)