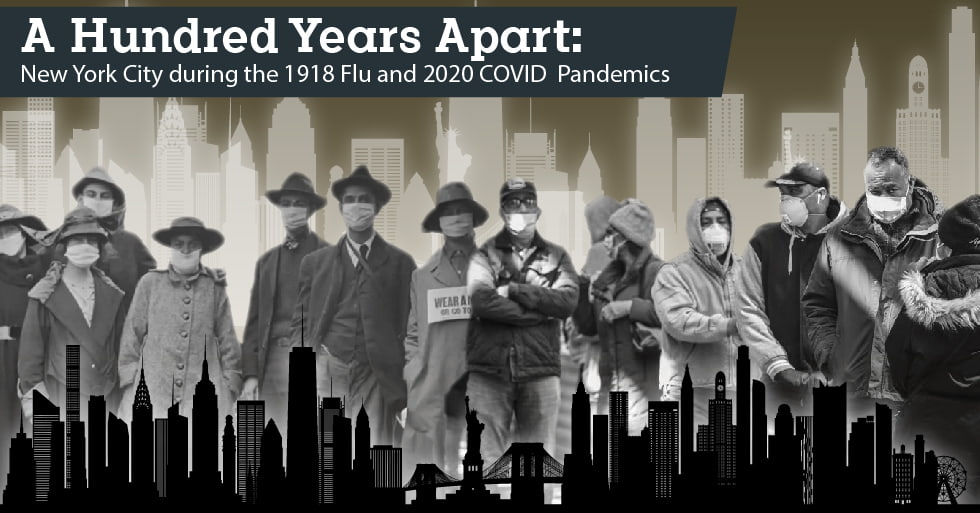

A Hundred Years Apart: NYC During the 1918 Flu and 2020 COVID Pandemics (Part 2)

Last week, we began our comparison of how New York City responded to a global pandemic a century apart. This week, we continue the comparison, this time looking at how schools, families, and Broadway balanced economic and health pressures, two essential concerts that were often at odds.

Last week, we began our comparison of how New York City responded to a global pandemic a century apart. This week, we continue the comparison, this time looking at how schools, families, and Broadway balanced economic and health pressures, two essential concerts that were often at odds.

1918 | Schools were kept open for the duration of the Epidemic, as Health Commissioner Copeland considered schools a safer environment for the city's children than their respective homes. In doing so, teachers began a presumptive roll as health monitor and contact tracer, with Copeland claiming that "In schools the children are under the constant guardianship of the medical inspectors. This work is part of our system of disease control. If the schools were closed at least 1,000,000 would be sent to their homes and become 1,000,000 possibilities for the disease. Furthermore, there would be nobody to take special notice of their condition."

| Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. "Tenement apartment" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1908 - 1921. |

This concept of schools being safer than the student's respective homes derives from the city's notorious tenement buildings, which provided up to three quarters of the city's one million children with housing. These tenements tended to have a higher population density than anywhere else in the country, with tenements in the Lower East Side ranging anywhere from 665 to 1,000 people per acre, compared to only 136 per acre in the same region as of 2010.

This density, when combined with a lack of clean drinking water and toilets, makes Copeland's decision not to close the entire school system down more understandable, especially considering New York's public schools were often considered some of the nation's best at the time.

Commissioner Copeland also targeted schools for the dissemination of educating the public in the form of pamphlets and leaflets explaining how the disease spreads, and ways in which to contain it. By handing the flyers to the city's students, the hope was they would make their way home, and therefore spread continued awareness and knowledge about the disease to the public more efficiently.

2020 | This Fall, New York has opted for a mix of in-person learning and remote instruction due to the uncertainty of the trajectory of the virus, though this has presented its own logistical challenges relative to ensuring the city's entire population of students has both a computer and stable internet access. So far, the Department of Education has disseminated over 320,000 iPads complete with internet access, though some public schools still lack the necessary devices needed to connect all their students.

The loss of traditional in-person instruction has also compromised the food security of many families who rely on school lunches to feed their children. An estimated 1.5 million New York City residents face some sort of food insecurity every year, including a quarter of all the city's children. The city has responded by providing a $420 food benefit card to each family associated with a New York Public school student, though many families are still likely to struggle considering the ongoing unemployment crisis in the city, where over one million are out of work, with the city's unemployment rate remaining over twice the national average.

1918 | Broadway, much like the city's public schools, remained open not only in an attempt to further spread influenza related knowledge to the public, but, from Commissioner Copeland's perspective, to retain a sense of order and normality among the populace. The theaters, like most businesses in the city, were subjected to new requirements in an attempt to limit the spread of the influenza, from banning children under 12 from attending to keeping the doors and windows to the theatre open during down time between shows. Similar to the schools which were seen as safer than the home, the city's theaters were considered essential in order to prevent mass hysteria and panic resulting from the other lockdown procedures already making themselves felt throughout the city.

2020 | It has been nearly 8 months since the last Broadway performance, with the reopening timeline listing June of 2021 as the earliest date for widespread reopening. Much of the city's actors and artists face historic unemployment, as many lost their jobs not only in the performing arts, but in the restaurant and service industries that often provide them with additional financial security. While some theaters have switched to online programming, it remains to be seen how much of the venues in New York will survive the coming months.

New York, especially compared to America's other large cities of the time, weathered the epidemic relatively well, with a much lower fatality rate despite its unique population density. Still, by the end of the epidemic around 20,000 New Yorkers had lost their lives, out of a population of roughly 5.6 million. Compare that to today, where the city currently lists around 24,000 deaths out of 8.4 million. New York's first death to COVID-19 occurred on March 14th of 2020, meaning the city is currently in its 7th month fighting a pandemic. But with cases ticking upwards once again, the masks now ubiquitous on both the sidewalks and subways of New York show no sign of being taken off anytime soon.

Henry Trinder is a writer and musician living in Greenpoint, New York.

![EOScu Logo - Dark - Outlined [07182023]-01](https://blog.eoscu.com/hubfs/Eoscu_June2024/Images/EOScu%20Logo%20-%20Dark%20-%20Outlined%20%5B07182023%5D-01.svg)