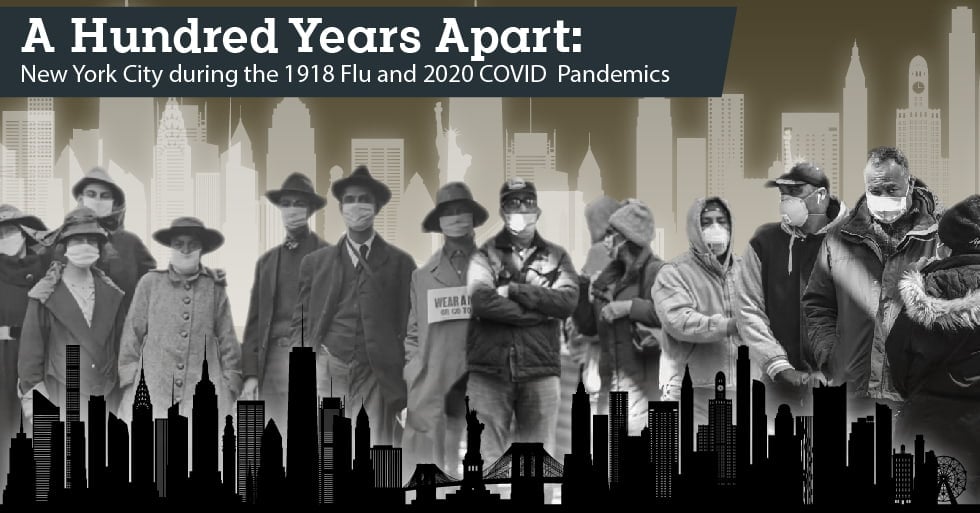

A Hundred Years Apart: NYC During the 1918 Flu and 2020 COVID Pandemics

In November of 1918, a New York City subway car crashed in Flatbush, Brooklyn, killing 100 passengers and injuring 250 others. Photos of the wreckage show a wooden train twisted and bent along the tracks, with the New York Times describing the aftermath as “a darkened jungle of steel dust and wood splinters, glass shards and iron beams projecting like bayonets.” The train operator, Antonio Luciano, was but 25 years old at the time, and initially attempted to walk away from the crash, himself uninjured. It was only after intensive media coverage of the incident and the resulting lawsuits that it was eventually revealed Luciano was at the time recovering from a bout with the Spanish Flu, which had just days before claimed the life of one of his daughters.

By the time the Spanish Flu came to New York City in 1918, the city was sprawling. Not only was it the largest city in the United States, it was well on its way to becoming one of the largest cities in the history of the world. This New York of a hundred years ago is more recognizable than most might think. You could still catch a cab to a Broadway show, the Village was still the epicenter of Bohemian culture, and the subway, with an annual ridership of around one billion (in a world with approximately 1.8 billion inhabitants), was still the preferred method of transportation for much of the city's inhabitants. But perhaps the most surprising aspect shared by the New York of 1918 and of today is the presence of a fatal epidemic threatening to upend much of what makes the city so unique, and consequently so vulnerable.

|

|

|

“How Disease is Spread/Sneeze but Don’t Scatter” published on November 9, 1918. Collection of New York Municipal Archives. |

Prior to the initial wave in fall of 1918 of the Spanish Flu, the city already had extensive history dealing with tuberculosis, which had fallen to a mortality rate of around 130 deaths per 100,000 individuals from a high of 425 deaths per 100,000 in the 19th century, an 89% decrease. The city's Health Commissioner at the time, Royal S. Copeland, began his response to this new influenza with confidence developed through the city's previous battle with tuberculosis, invoking personal and maritime quarantines, restricting business hours, and educating the public on the dangers of this new strand of influenza, and what they can do to hinder its spread.

Infrastructure: 1918

Whereas the New York of today sits surrounded by three major airports, the main influx points of 1918's New York were the docks. Hundreds of piers once jutted out along both the Hudson and East rivers, playing host to thousands of ships and their passengers everyday. This presented a novel challenge for the city's port officials, who as early as July 1918 began disease surveillance measures with the hopes of targeting symptomatic individuals, isolating them in the city's hospitals, and carrying out additional contact tracing for the ship's sailors.

Three ships specifically, the Norwegian Bergensfjord, the Dutch Nieuw Amsterdam, and French Rochambeau, are often thought of as the harbingers of the initial wave of the influenza. According to the CDC, those afflicted with the Spanish Flu were likely to develop symptoms within just one to four days, while COVID-19 can conversely can take up to two weeks, leaving a greater likelihood of asymptomatic spread. For health specialists at the time of the Spanish Flu, this meant it was easier to separate the sick from the healthy, with shorter quarantine times overall compared to the standard two weeks of today. As these three ships came into New York Harbor, attempts were made to isolate the symptomatic sailors within local hospitals as quickly as possible, but this wasn't enough to prevent the spread among the Naval community, and soon the entire port of New York was placed under a general quarantine on September, 12th of 1918.

Complicating the quarantine procedures further was America's involvement in World War I, and New York's status as the point of departure for much of America's armed forces heading to Western Europe. While ships were previously held at port in quarantine before landing, New York's strategic military importance meant previous quarantine protocols were augmented in order to keep supplies and soldiers moving in and out of the harbor. In the summer of 1918 Health Inspectors began boarding the ships themselves, thus allowing the ships to dock immediately, maintaining the harbor's economy and movement.

Infrastructure: 2020

During the COVID-19 Crisis, New York City emerged as an early hotspot in the United States, meaning temporary travel restrictions were put in place in effort to quarantine those leaving the City for other states, although that has now been reversed, with New York requiring travelers entering the state and city from countries/states with high infection rates to quarantine for 14 days upon arrival, whether that be by plane, car, or train.

Within New York itself, the subway has seen a drastic reduction in ridership, as high as 90% in some cases. Subway service is now regularly withheld overnight from 1-5am, as trains are cleaned and sterilized for use the following day. Over the summer MTA buses became fare free, in an attempt to both maintain a sterile environment for the bus drivers and provide essential workers who rely on public transport reliable transportation at all hours. The long-term impacts of COVID-19 on the infrastructure of NYC will become clearer as time goes on, especially as the second wave of the virus arrives with colder weather.

In our next post, we'll explore how schools dealt with a pandemic, one hundred years apart.

Henry Trinder is a writer and musician living in Greenpoint, New York.

![EOScu Logo - Dark - Outlined [07182023]-01](https://blog.eoscu.com/hubfs/Eoscu_June2024/Images/EOScu%20Logo%20-%20Dark%20-%20Outlined%20%5B07182023%5D-01.svg)